Two Girls Down, by Louisa Luna

Plot:

Louisa Luna opens her novel Two Girls Down with the kidnapping of two sisters, Kylie and Bailey, ten and eight years old. Their mother has popped into a K-Mart for a few minutes, leaving the girls in the car. When she returns, the girls are gone. Frantic search. Police. Code Adam alert. Nothing. No trace. Enter Alice Vega, wild woman, free-lance missing-person finder, and Cap, ex-cop turned private detective. Vega became an overnight star when she recovered a high-profile child, and has been in demand ever since by people whose loved ones have disappeared. The police are not happy to have her involved in the case.

The grandmother of Kylie and Bailey asks Vega how many of the children she has she has gone after have been successfully found. Vega tells her all of them. One hundred per cent. The caveat, and the terrifying reality that drives the tension in the novel, is that not all were alive when she found them, and a few who were found alive were dead in other ways, scarred beyond repair by the experience.

When Vega calls on Cap to help her find Kylie and Bailey, the search lures him from his relatively safe and boring work breaking up bad marriages exposing unfaithful spouses. As an ex-cop, he is capable of handling the danger of the job Vega offers him, and the possibility of a little excitement stirs some of the old cop adrenalin.

Writing:

Luna’s writing is strong. When we first meet Vega, she is doing a yoga handstand and thinking about the danger of not knowing what is just beyond your vision. “Her old boss in fugitive recovery, Perry, used to call it Little Bad and Big Bad. Little Bad was the teenager on the front porch with a Phillips screwdriver tucked into his pants. Big Bad was his daddy waiting inside with a loaded .38 and a pissed-off pit bull. There was always a worse thing that you couldn’t see, and it was closer than you thought.” When Cap meets the mother of the lost girls at a bar for an interview, the narrator tells us, “He looked at Jamie’s hands on the bar, lying there like leaves of a dead plant, and did not extend his.”

Characters:

Though the writing style is strong, the strongest element of the novel is the characters. The two leads are interesting and complex. Luna vividly draws the supporting characters—the mother, Cap‘s daughter, the police—who are strong in their own right. Cap‘s daughter, Nell, is, in fact, almost a show-stealer—smart, sassy, loving.

Pace:

The pacing in Two Girls Down is compelling. The build-up is quick, with the kidnapping kicking the conflict into gear immediately, and the intensity develops steadily right up to the powerful ending. I’d compare it to Black-Eyed Susans, by Julia Haeberlin (See my review here). And laced through the action and suspense, Louisa Luna offers the reader the possibility of romance. What more can you ask?

Paragraph

The Black-Eyed Susans, by Julia Heaberlin

“The Susans are a greedy plant, often the first to thrive in scorched, devastated earth.” This line, early in Julia Heaberlin’s novel Black-Eyed Susans, works on more than one level and becomes an underlying motif for the narrative. Tessa Cartwright was raped and left for dead as a teenager among a field of flowering black-eyed Susans. The bones of other long-lost girls surrounded her. In the media coverage of the case, she and the other girls become known as the Black-Eyed Susans. Out of her scorched and devastated life, Tessa has managed to thrive.

Tessa:

The attack itself remains an empty spot scorched in Tessa’s memory. The novel opens years later, when Tessa has a teenage daughter of her own. She is working with an attorney and a forensic scientist to free the man convicted of the crime, who sits on death row awaiting imminent execution. Though she can’t remember the attacker, she has become convinced that her testimony at the trial sent the wrong man to death row. Underlying the race to save the condemned man is the possibility that the real killer is now stalking Tessa.

The Voices:

Two voices tell the story—the first-person voice of the present-day Tessa, and the first-person voice of her earlier self, the young Tessie in the months after the attack. The voices alternate in short chapters of three to five pages, creating a dynamic pace in the complex and gripping narrative. The two narrative voices press against each other, one from the past and one from the present. The tension grinds inevitably toward the final revelation, squeezing out the truth that lurks behind the Black-Eyed Susans.

Supporting Cast:

Tessa’s teenage daughter, the defense lawyer, and the forensic scientist are engaging and well-developed characters and become important pieces in solving the puzzle, as does Tessa’s best friend from childhood, who disappeared years earlier after the trial. And always, the voices of the other Susans in Tessa’s head, the dead girls who encourage, warn, and challenge her.

Conclusion:

Some readers may find the resolution of the mystery a bit contrived, maybe a little far-fetched. I did. But that won’t take away from a really good story told very well. As in the case of the Nordic Noir novel Sun and Shadow, by Ake Edwardson, the flaws do not outweigh the strengths. I don’t hesitate to recommend the book.

An Artist of the Floating World, by Kazuo Ishiguro

Introduction: Ishiguro

Memory and the heart. Such fragile things on which to build our notion of ourselves. As the old prophet Jeremiah said, “The heart is deceitful above all things . . . Who can understand it?” And memory is surely at least as deceitful as the heart. Both memory and the heart seem to function at the mercy of the transient, ephemeral world of human life. And they are central to the fiction of Japanese writer Kazuo Ishiguro, who just won the 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature.

An Artist of the Floating World is a beautiful emotional set piece. Following World War II, an aging Japanese artist struggles with his experience of post-war Japan. In time, he regrets his role in the rise of empire that ended in the destruction of the old world.

Comparison: Remains of the Day

Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins in Remains of the Day.

It may be that most people know Kazuo Ishiguro for his novel The Remains of the Day and its film adaptation, with Anthony Hopkins as the butler Stevens and Emma Thompson as Miss Kenton. In fact, there are significant similarities in tone and theme between the two novels. In both cases, the main character looks back on a career in which he devoted his life to a cause that was later shown to be horribly mistaken and in which he turned his back on a path that would have resulted in a different, and probably more fulfilling life. Mr. Stevens, in The Remains of the Day, does not marry Miss Kenton. In An Artist of the Floating World, the artist Masuji Ono turns his back on “fine art.” Fine art focuses on the fleeting beauty of this world. Ono makes his art serve the empire of the “New Japan.”

Conclusion: Catharsis

Both novels come from a perspective not long after the war. The protagonists look back on a time prior to and during the war, blended with their current lives. The tone of both is nostalgic, beautiful. In An Artist of the Floating World, Ishiguro’s use of an unreliable narrator, whose growth in the novel is toward self-realization, is masterful. Numerous times in the narrative, the artist Ono says it is entirely possible that his memory of an event or conversation is not accurate, that things might not have happened exactly as he presents them. These admissions become part of his growth in awareness of self. They are some of the elements that make him sympathetic and human, and very like all of us.

A reader who identifies with Ono, and feels compassion for him, may experience in reading this novel what Aristotle called catharsis in his Poetics, a vicarious purging of guilt and fear, the impetus toward self-understanding. (See Aristotle on Character) Ishiguro seems to be saying that as we grow older, we come to realize how much of our image of ourselves is dependent on feeling and memory, and we come to understand how fickle, how deceitful, those things can be. If we are to live in peace with ourselves, we must see ourselves honestly and forgive ourselves. We have all committed well-intentioned errors in our pasts. Only with honesty and forgiveness can we live with integrity and dignity.

Sun and Shadow, by Ake Edwardson

Overview

Sun and Shadow, the first Detective Erik Winter novel by Swedish writer Ake Edwardson to be translated into English (1999), is a dark psychological mystery that chronicles two grotesque double murders and the exhausting investigation that follows. The plot is complex, and it delivers the build-up to a suspenseful ending. (See review of The Preacher, by Sander Jaboksen)

Edwardson’s Style: Dialogue, Description, Verbs, Filtering

Dialogue-

Edwardson’s style is literary. The writing is strong, especially the descriptive language and the dialogue. After Detective Winter visits his father, who has just had a heart attack and with whom Winter has had a strained relationship, he tells his lover, Angela, about it:

“ What was it like, seeing him again?”

“As if we’d been chatting only last week.”

“Sure?”

“Depends what you mean. We spoke about safe subjects.”

“Everything takes time. He has to get better first.”

“Hmm.”

“Are you tired?”

“Not so tired that I can’t indulge in a glass of duty-free whiskey. What about you?”

These spare conversations, circling around a subject like a dance, are common. In effect, dialogue carries the narrative.

Description-

Edwardson avoids extensive descriptive passages that tend to slow the narrative movement. Yet often the descriptive language is strong. Here is an example of a strong and spare description:

“It was night in the apartment, no lights burning anymore. A standard lamp had been on all day, but the bulb had gone. As dawn broke, autumn sidled in through the venetian blinds and a roller blind in the bedroom let in patches of light.”

I would quibble with a couple of things (pet peeves of mine) in Edwardson’s style. (I should add here that it’s entirely possible that the first of these problems results from translation and may not exist in the original.)

Verbs-

First, Edwardson works the poor, overused verb “to be” to within an inch of its life, both as the main verb in a sentence and as the helping verb used with a main verb in the “–ing” (progressive) form. I’ll italicize examples in the following short paragraph to demonstrate:

“Winter was walking along the Ricardo Soriano. It was evening again. He went into the cerveceria Monte Carlo and ordered a glass of draft beer at the bar. The place was full of men watching a football match on a large screen. Real Madrid versus Valladolid. He drank his beer and felt comfortable among all the shouting. There were no women inside the bar. They were sitting at tables on the pavement outside, waiting for the match to end and the evening to begin.”

Five “to be” verbs in a short paragraph. The problem: All these “to be” verbs kill the immediacy of the reader’s experience of what happens. Compare the following possibilities: “Winter walked along . . . “ or “The bar overflowed with men watching . .” or “All the women sat at tables on the pavement outside . . .” Revising “to be” verbs into action verbs is a staple of good writing.

Filtering-

My second quibble: Edwardson tends to filter sense experience instead of giving it to the reader directly. Here’s what I mean. Detective Winter goes into a bar, and the narrator tells us: “Winter could hear people speaking Norwegian, Swedish, and German.” The readers should experience the bar, not have Winter experience it for them. It would be easy to revise this passage to say, “People at the tables around him spoke Norwegian, Swedish, and German.” That way the reader experiences the polyglot with Winter instead of being told that Winter experienced it. This kind of filtering is too common in the novel.

Summary

Okay, with all that said, this book was a good read. I recommend it, especially for fans of Scandinavian crime fiction. It’s a strong example of the genre. The complex plot builds slowly and in the end delivers a powerful, driving finish.

Missing Person, by Patrick Modiano

The Novel:

What is possible when the missing person you seek is you? Where are the clues that will lead you to yourself? Only in the past. The past, for the protagonist of Patrick Modiano’s novel Missing Person, is the period of the German occupation of Paris prior to and during World War II. It is a past of which, when the novel opens, he remembers nothing. He suffers from near total amnesia., He has lived a decade as a private detective, solving other people’s mysteries, under an identity provided by his boss. He is Guy Roland. As the novel opens, his boss retires and closes the agency, and Roland begins to investigate his own identity. “I am nothing. Nothing but a pale shape, silhouetted that evening against the cafe terrace, waiting for the rain to stop; the shower had started when Hutte left me.”

And so begins the journey from nothing to something. The novel projects the irony of the detective searching for himself. All those he meets know him, but he knows none of them. His memory begins to return in bits and pieces, brief snatches of the past. And he discovers at the heart of his search for himself a dark secret, gradually revealed. His role in the disappearance of someone very close to him.

The Author:

Patrick Modiano won the 2014 Nobel Prize for Literature. Missing Person is an early novel (1978), but it embodies the themes for which Modiano has become known—the power of the past and the search for identity. The prose in this short novel (under 200 pages), while exploring these themes, exhibits his beautifully crafted style and his haunting, melancholy tone.

His protagonist says, “I believe that the entrance-halls of buildings still retain the echo of footsteps of those who used to cross them and who have since vanished. Something continues to vibrate after they have gone, fading waves, but which can still be picked up if one listens carefully. . . [I omit a phrase here to avoid a spoiler.] . . . I was nothing, but waves passed through me, sometimes faint, sometimes stronger, and all these scattered echoes afloat in the air crystallized and there I was.”

Beautiful stuff.

Rating:

I loved reading this novel, like slowly eating a perfect lasagna, or ravioli, with a glass of good Cabernet. You chew each bite slowly and savor it. I would have liked to give Missing Person an unqualified 5-Star rating, but when I got down to that last bite, I found it beautiful but unsatisfying. The tone of the short final chapter is exquisite, and the final two sentences are stunning. But alas the resolution of the story was left open-ended, and I confess I felt betrayed.

I highly recommend this novel to anyone who loves finely crafted style in literature and the deep exploration of human identity. Those looking for high action will be disappointed.

The Preacher, by Sander Jakobsen: Nordic Noir in Clear Prose and Diffuse Plot

The Preacher, a Nordic Noir mystery/thriller by Dagmar Winther and Kenneth Degnbol, a.k.a. Sander Jakobsen, offers a beautiful prose narrative. Not surprisingly for Scandinavian crime fiction, the style leans toward the literary. It tells the story of two murders, each of a woman, apparently unrelated. As the police draw closer to solving the first, they realize the second is indeed closely related.

Style:

The novel opens with the murder of the wife of the vicar of a small Danish village. The writing is evocative throughout. After the investigative team has finished their work, “Then, once again, calm spread its wide blanket over the vicarage.” And as the vicar stands looking over the disarray, “His body had sensed and recorded it, the distance to reality dulled by death itself.” He walks around the house observing all the little memorabilia of his dead wife. They are like “treasures in a museum, when Karen’s death in small incomprehensible bits invaded and claimed him.” The style here reminds me of Thomas Enger in his novel Cursed (See my review here).

Characters:

The main characters—Thorkild, the vicar; Frank, the brother of the second murder victim; Birgitte, the old girlfriend who moves in with the vicar to take care of him after his wife’s murder; and Thea, the detective from Copenhagen, who is drawn into the case emotionally as well as professionally—are well developed, very human, and sympathetic. The reader pulls for them, identifies with them.

Point of View and Plot:

If I have complaints about the novel, they have to do with point-of-view and plot. The point-of-view is third person subjective, alternating between all the main characters and even some of the lesser ones. As a result, the reader struggles to find a sympathetic center. The title, The Preacher, leads the reader to assume that the vicar is intended to be that center. But, in fact, the detective, Thea, often steals that role. The problem becomes that none of the characters take control of narrative perspective. In the end, the point of view is diffuse and unsatisfying.

This diffuse p.o.v. reflects, and to some degree creates, a diffuse narrative structure as the novel attempts to juggle and maintain several competing plot lines—solving the first murder, solving the second murder, the relationship of Thorkild and Frank, the relationship of Thea and Thorkild, and the role of the killer in all of these. I began to feel like a ping-pong ball, going back and forth, never landing on a narrative thread I could anchor everything to. The title role of the novel—the role of “Preacher”—can ultimately apply not only to the vicar, but to Frank, who preaches an angry laissez faire philosophy, or to the killer, who “preaches” a Nietzschean doctrine of the Superman. At times the “preaching” overcomes the narrative drama.

BUT, in spite of all this, I consider the novel a good read. The problems are technical, and perhaps my pet peeves, rather than total failures in the story.

Watch Me Disappear, by Janelle Brown

Janelle Brown’s latest novel, Watch Me Disappear, due out July 11, is a gripping read. A mother’s disappearance while on a solo backpacking trip in the mountains of California devastates her husband and daughter. The narrative is beautifully imagined and intricately woven. The plot is driven by love, loss, and lies. Those three forces pull the characters in opposing directions, making them doubt everything they thought they knew. The father, Jonathan’s, love drives him to write a romanticized autobiography of his life with Billie, the lost wife. As events unfold, he begins to doubt that he ever knew her. The daughter, Olive’s, love causes her to see visions of her lost mother, calling Olive to find her. But she finds much more than she thinks she is looking for. The narrative of Watch Me Disappear is filled with unexpected turns that make the reader not want to put the novel down. And the surprises never stop coming. The characters are complex and sympathetically drawn, very real people with traits that make you love them and traits that make you hate them.

Janelle Brown’s writing is stunning. Beautiful descriptions, surprising images (“an ominous premonition spiders up the back of his neck”), pithy insights into human nature and the beauty and tragedy of life. An old woman who answers the door: “Her hand is papery and porcelain-thin on Olive’s own.” Descriptions that make your skin crawl: “He left an impression of stubble and flannel and stringy unkempt hair, and a sharp smell, something itchy and intense oozing from his pores.” At times the language itself creates a moment of comic relief: “As Isaac tongued her molars, Olive kept visualizing the slides of amoeba they were studying in her biology class–his germy pseudopods spelunking in her mouth.”

Watch Me Disappear is an engaging and rewarding read.

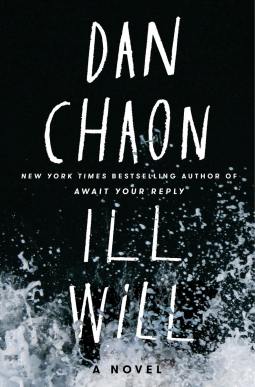

Ill Will, by Dan Chaon

Not for the Faint of Heart

Dan Chaon‘s book Ill Will is a beautifully written, dark, at times almost lyric portrayal of a man’s struggle to discern what is real and to confront his past. He is a therapist who grew up with a disturbed, abusive older adoptive brother, and whose parents were brutally murdered when he was a teenager.

Chaon’s novel follows two plot lines, the disintegration of the therapist’s own family after his wife dies, and the bizarre investigation by the therapist and one of his patients of a series of deaths. Told from multiple points of view and shifting frequently between past and present, the narrative is complex and engaging. It moves toward its conclusion driven by the inescapable, inexorable power of the past to control the present. The characters’ journeys are downward spirals right from the beginning.

Chaon offers a dark, almost despairing view of human nature. This book is not for the faint of heart.

The Locust Diagrams, by Nate Parker

The Locust Diagrams, Nate Parker’s first book of poetry, from Noemi Press, is a wild and surprising romp through language and imagery. If your tastes tend toward traditional, rhymed, easily accessible poetry, then The Locust Diagrams will not make you happy. But if your tastes have a ragged edge, if you believe that sometimes poetry has to surprise you into loving it, and if you like a little twisted humor, then Nate’s first book is for you. Here are the opening lines of the first poem in the collection, “Tender”:

“how we eat glazed donuts/ on the traintracks/

over the river, share dark/ bean coffee while larks/

headbutt our sugary feet/ & sunlight fills the woods/

& sears the dew.”

These seven lines are packed with beauty and surprise. Sharing donuts on the train tracks “while larks/ headbutt our sugary feet.” What a beautiful surprise of an image, but it’s followed by a very traditional image–“sunlight fills the woods”–which then turns into another stunning surprise when the sunlight “sears” the dew. The choice of that verb, “sears,” in that situation is the mark of a really fine poet. It surprises and at the same time is the perfect word.

One more example, the opening lines of a poem titled “Children Camping”:

“wind out of Michigan/ shoots/ pine needles

into a light pink/ fat rapt/ creek,

sweetening it down to its slugs.”

Again the images are a fun mixture of traditional and startling. The wind out of Michigan doesn’t “blow” the pine needles; it “shoots” them into the creek–a “light pink fat rapt creek” no less–and the needles sweeten the creek “down to its slugs.” The verbs “shoots” and “sweetening” here, like the verb “shears” in the earlier example, are more marks of real poetic vision.

Some of the poems in the collection are more abstract, more post traditional, in form and language than the examples above. But the beauty, the surprise, the unusual, sometimes eccentric, view of the world is always there.

Support poetry. Get a copy.

The Queen of the South, by Arturo Perez-Reverte

How’s this for the opening line of a novel: “The telephone rang, and she knew she was going to die.” Come on, admit it, you wish you had opened a novel that way. I wish I’d written that line as an opening. But Arturo Perez-Reverte wrote it to open his novel The Queen of the South. It’s a pretty good hook line, the kind of line that will buy you at least a few pages from the reader. But only a few. You have to sink that hook deeper and start reeling in the line—get the reader committed to reading the rest of the story. In other words, sometime soon, you had better be offering either some scintillating action (for one kind of reader) or some luscious prose (for another kind of reader).

Maybe one of the reasons that Perez-Reverte’s novels have sold millions of copies in a bunch of languages is that, maybe for a third kind of reader, he does both—after hooking the reader immediately, offering action and style. That third kind of reader wants to be wooed by the language, made love to by the sounds of the words and the beauty of the imagery and the surprise of really interesting characters, but also enjoys the thrill of the mystery.

Perez-Reverte is known as a writer of “intellectual mysteries,” set in specialized worlds such as art restoration, chess, or fencing. The narrator of The Queen of the South is an ex-journalist who has become a novelist, whose latest work, which is biographical, is set in the world of international narcotics smuggling.

Honestly, I’m much more interested in the specialized worlds of art restoration, chess, and fencing than I am the world of international narcotics smuggling, and so this novel has to sell me. Here’s a sentence from page five that helped set the hook for me: “Then she turned toward the rain that was pattering against the windows, and I don’t know whether it was something in the gray light from outside or an absentminded smile, but whatever it was, it left a strange, cruel shadow on her lips.” Okay, I want to know more about that woman. The hook is set and Perez-Reverte is reeling me in. In fact, “that woman” is the biographical focus of the narrator. But Arturo Perez-Reverte has long ago convinced me, in three of his other novels, that he will deliver a literary, intellectual mystery, and that I will love it. So I guess I’ll go with him on this one too.

The Flanders Panel, by Arturo Perez-Reverte

I just finished reading my second Arturo Perez-Reverte novel, The Flanders Panel. Perez-Reverte’s novels use many of the standard elements of the mystery genre, but are written in a rich style, beautiful even in translation, and explore the deep humanity of his complex characters. I’ve started a third Perez-Reverte novel, The Fencing Master, and one of the things I like most about these three novels is that they are all set in a specialized subculture–rare book collectors, art collectors, professional chess, fencing.

The protagonist of The Flanders Panel, a young woman who does restoration work on classic pieces of art for some of the biggest collectors and art houses in the world, uncovers a long hidden secret about a major Renaissance painting on which she is working. Her world begins to fall apart, and her life is threatened. Her response, as given by Perez-Reverte’s narrator, intrigues me:

“Was she really afraid? In other circumstances, the question would have been a good topic for academic discussion, in the pleasant company of friends, in a warm, comfortable room, in front of a fire, with a bottle of wine. Fear as the unexpected factor, fear as the sudden, shattering discovery of a reality which, though only revealed at that precise moment, has always been there. Fear as the crushing end to ignorance or as the disruption of a state of grace. Fear as sin.”

This paragraph, beautifully written, posits the powerful tension between two ways we experience reality–emotion and intellect. In this case, fear, the primitive fear of death, of violence, of pain, is the physical experience. This fear in the protagonist’s gut becomes anger, the desire for revenge, the fight for self preservation. But that same fear in her mind becomes metaphor–the “crushing end to ignorance,” the “disruption of a state of grace,” or, most surprising, “sin.”

We all respond to fear on the emotional level with “fight or flight.” We respond to fear on the intellectual level with metaphor–it becomes a bottomless chasm, a stampede of wild horses, or Hell. I wonder whether, as we evolved from pre-conscious beings to beings that are self-aware, our experience of fear began to operate on two levels. The paintings on the cave walls at Lascaux in southern France, over seventeen thousand years old, were metaphors for the visceral experience of hunting large and dangerous animals. Perhaps we make metaphors of our deepest fears so that we can live with them.

What does it mean for fear to be the “disruption of a state of grace,” to be “sin”? Do we live in the illusion of security, and is the illusion of security the state of grace that is disrupted by the threat of violence or death? If so, then “state of grace” is itself a metaphor, a metaphor of an illusion. All of us who have lived beyond our teenage years have come to understand that in this life there is no security, that everyone, from the pauper to the prince, is subject to sudden and unexpected dangers, to violence of various forms, to death. And yet most of us, from day to day, live as if this were not true. An odd way of looking at “grace”–the self-imposed ignorance of the fragile, the delicate, splintery nature of life, that is beyond our control.

Hard not to hear echoes of the story of the Garden of Eden. Adam and Eve living in ignorance, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, The Fall as the sudden confrontation with nakedness and death. John Milton opens Paradise Lost with this: “Of Man’s First Disobedience, and the Fruit/ Of that Forbidden Tree, whose mortal taste/ Brought Death into the World, and all our woe,/ With loss of Eden . . . . Sing Heav’nly Muse.” Perez-Reverte’s The Flanders Panel becomes another version of that primordial story. A paradise lost. And Perez-Reverte? Sing, Heavenly Muse!

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, by Richard Flanagan

Richard Flanagan’s novel The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which won the Man Booker Prize for Fiction in 2014, describes the incomprehensible horror of a prisoner of war camp along the infamous Burma “death railroads” in World War II, and the stunning beauty of human compassion, sacrifice, and love. He offers a deeply complex vision of humanity. The novel is stout stuff, not for the feint of heart, but if you can weather the unblinking treatment of human suffering, the reward comes in Flanagan’s profound compassion and deep understanding of the human condition–and in his beautiful prose.

Flanagan’s title comes from Matsuo Basho’s late 17th-century travel journal with the same title, describing a 1500 mile journey by foot into the far north of Japan. Basho was a master of the haiku form, through which he communicated the beauty and transience of life and the frailty of all living things. When I was teaching at the university, my World Lit students read Basho’s journal under the alternately translated title The Narrow Road of the Interior. Flanagan’s novel has strong thematic echoes of Basho’s work. Here’s a very Basho-like statement from deep in the novel: “Humans are only one of many things, and all these things long to live, and the highest form of living is freedom: a man to be a man, a cloud to be a cloud, bamboo to be bamboo. . . . People kept on longing for meaning and hope, but the annals of the past are a muddy story of chaos only. . . . Of imperial dreams and dead men, all that remained was long grass.”

I fell in love with the protagonist, Dorrigo Evans, an Australian doctor, when as he lay beside a beautiful woman in the night, Flannagan’s narrator says: “A good book, he had concluded, leaves you wanting to reread the book. A great book compels you to reread your own soul. . . . He believed books had an aura that protected him, that without one beside him he would die. He happily slept without women. He never slept without a book.”

One of the magical things about the novel is that it turns a harrowing story about suffering and death in a prisoner of war camp into a book about love–between men and women and between men caught in an unimaginable horror. Late in the novel, when after the war Dorrigo Evans is meeting with the wife of one of his men who was killed in the camp, she says to him: “Do you think that’s what we mean by love, Mr Evans? The [musical] note that comes back to you? That finds you even when you don’t want to be found? That one day you find someone, and everything they are comes back to you in a strange way that hums? That fits. That’s beautiful.”

Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North made me hum, it made me ache, it made me sigh. As a writer, it made me jealous and happy at the same time. If your nerves are steady and your stomach strong, you have to read this novel. It will get hold of you and make you hum.

The Club Dumas, by Arturo Perez-Reverte

I’m humming, like a tight-wire in a high wind. A few minutes ago I finished reading a book that tasted like honey and red wine, that punched me right in the mouth and dared me not to like it, that made such love to me I cried “I’m melting!” So somebody’s got to read this book and talk to me.

Arturo Perez-Reverte, a television journalist born in Cartagena, whom I had never read and didn’t know existed, has written three novels, and now I want to read the other two. This novel, The Club Dumas, is a bibliophile’s delight–a literary mystery set in the underworld of serious book collectors and the mercenaries who serve them, with a strong dose of the occult thrown in. The title alludes to the 19th-century French writer Alexandre Dumas, whose book The Three Musketeers plays an important role in the novel. The style reminds me of the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges and his labyrinths, cerebral, really smart writing, though this story is more accessible than some of Borges. And the characters are more human, more loveable than Borges’ tend to be.

I really like the main character, Lucas Corso, an imperfect, nearly dysfunctional, hero. Here is part of his introduction: “Corso was a mercenary of the book world, hunting down books for other people. . . . Jackals on the scent of the Gutenberg Bible, antique fair sharks, auction room leeches, they would sell their grandmothers for a first edition.”

I found the book at a book sale, decided to give it a shot, and bought it for fifty cents. Don’t you love it when that happens? Of course, I buy at least five book sale books for every one that turns to gold like this one did. But hey . . .

If you have read The Club Dumas, or if you are tempted to read it and give in to the temptation, let me know what you think. Meanwhile, I’m going on-line to find the first two novels.